Developer Experience (DevEx) is at the heart of how software teams work and thrive. It encompasses everything from the tools developers use, to the processes and workflows they follow, to the culture of the teams they work within. And at its core, DevEx isn’t just about productivity. It’s about empowerment, satisfaction, and the ability to do meaningful work without unnecessary friction.

In this asynchronous interview series, we explore DevEx through the eyes of the people who live it every day. I’ll be speaking with software professionals across roles and industries to uncover how they define DevEx, the challenges they’ve faced in creating good developer experiences for themselves and other developers, and the creative ways they’ve sought to improve the experience of developing software in today’s modern professional landscape.

Our second interview is with Platform Engineer Annabelle Thomas Taylor. We hope you enjoy the conversation!

Kristen: Thank you for agreeing to have this conversation about Developer Experience with me, Annabelle! I reached out to you for this interview really specifically because a few years ago, I got to watch you successfully transition from a software development role into a DevOps role, which I still think is just so impressive. I think it would be interesting to examine the differences between DevEx in those two different domains of shipping software.

Before we really get into it, though, can you tell the audience a little about yourself?

Annabelle: It’s lovely to chat with you, Kristen! I like to think of my professional experience so far as a meandering walk through the traditional development stack. I began as a front-end developer primarily focused on building data visualizations, and gradually began to wonder how my data got from Postgres to the browser. So, I took a full-stack role to find out. There I got a taste for backend programming, but also a load of questions about how and where we were actually deploying our applications. That opened the door to CI/CD, cloud infrastructure, container orchestration, and the rest is history. A classic “if you give a mouse a cookie” scenario (if we were giving mice Docker containers, I suppose).

Outside of work, I love playing the bassoon in my community orchestra, watching Jeopardy!, and hanging out with my toddler, Arthur. He’s really been on a board-book kick lately, so most evenings you’ll find us reading Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? for the umpteenth time. It’s always a party.

Kristen: Okay, I love that you have this “How does this work under the hood?” mindset, as reflected in your career story. I imagine this is part of what makes you an excellent engineer. A former colleague taught me the (totally positive) term “curious nerd”, and you, my friend, are a curious nerd! Meant as the highest compliment.

(Also, Arthur sounds delightful! I’ll be eager to know if your love of learning rubs off on him 😍)

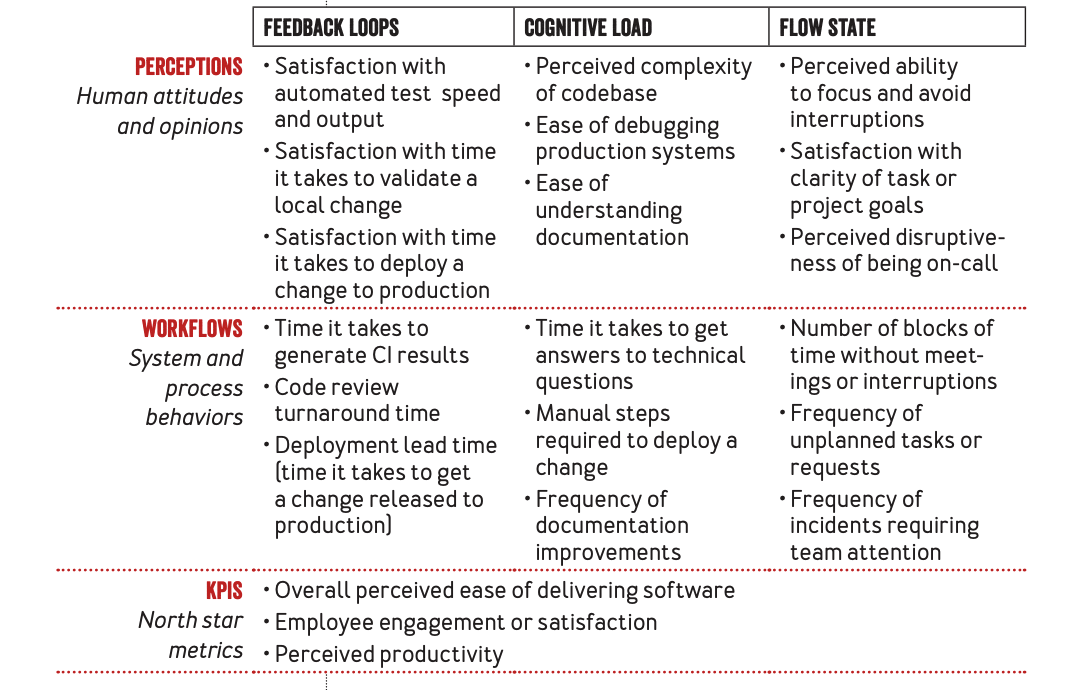

So, I think when a lot of people think about DevEx, they think about the factors that cause friction and frustration during the process of developing and shipping software. The authors of the original DX Framework have proposed a set of DevEx metrics centered around feedback loops, cognitive load, and flow state:

Image Source: DevEx: What Actually Drives Productivity, 2023

Image Source: DevEx: What Actually Drives Productivity, 2023

As the chart indicates, we can look at these three through the additional dimensions of human attitudes and opinions and system and process behaviors. Now, this chart isn’t exhaustive – these are just some examples - but I think they illustrate the kinds of things that can affect a software practitioner’s experience of building and shipping software.

In your experience, which of these DevEx factors are heavily shared between the software engineer/developer role and the DevOps engineer role? What factors do you feel are fairly distinct?

Annabelle: The flow state metrics really stand out to me as a shared DevEx factor, particularly “the perceived disruptiveness of being on-call.” In my experience as a DevOps Engineer embedded on product teams, there’s something of an open question as to who all should join the team’s on-call rotation. Often the question is framed as “are the alerts due to application code, or due to infrastructure?” but it isn’t always so cut and dry. As a toy example, let’s say an endpoint starts eating up memory, but there isn’t an autoscaling policy to handle that load or a health check to terminate the instance. Is that a “software problem” or a “devops problem?” Honestly, it’s kind of both.

The metrics around feedback loops resonate more with me when I wear my Software Hat, whereas those around cognitive load ring true for DevOps Annabelle. When I was working in a particular codebase every day, I had a much larger personal stake in, say, how long it took to run integration tests than I do now. I think it’s easy to fall into an “out of sight, out of mind” trap, and I try to stay cognizant of that.

Now, regarding cognitive load: once I took on a DevOps role I found myself relying on patterns across multiple applications to work through problems. Production issues don’t always happen in a vacuum. If one microservice is having trouble connecting to a central data store, it’s likely that other microservices are too (even if they aren’t monitored and observable, but that’s another can of worms). I try to lean on what I’ve learned from prior incidents when assisting in new ones, especially if I haven’t worked in that particular codebase.

I suppose a rough distinction that I’ve seen is “software friction occurs in depth, devops friction occurs in breadth.” And no one is having a good time when an alert goes off in the middle of the night.

Kristen: Amen to that, sister 😆

You mentioned that you “try to lean on what (you’ve) learned from prior incidents when assisting in new ones.” For me, one of the hardest parts of being a software engineer was having to remediate production failures; chasing down bugs that have brought down parts of the system (or the entire system!) can be high-stress, high-stakes, and involve lots of stakeholders peering over your shoulder, watching for progress, frequently asking for updates.

For me, this situation induces anxiety, and for me and many others, anxiety impedes learning (lots of research around this in multiple domains). And so something I’ve found in my career is that some of the systems I have to use to debug and track down production-system issues are ones that I’m really only interacting with when there’s a production issue.

I’m curious: Do you engage in any kind of focused learning in order to prepare yourself for the big, high-stress fires that sometimes occur and that – as a DevOps engineer – you’re often pulled in to help address?

Annabelle: I actually feel a bit sheepish in answering. In short, I don’t. I used to attempt what was very unfocused learning to prepare for incident response, but that just looked like frantically jumping from intro doc to 101 video to blog post about a smattering of technologies, then panicking when it wasn’t all immediately clicking. I felt like I needed to be prepared for anything, but that isn’t realistic. There will always be something in an incident response that surprises you.

I think I actually got a lot better at incident response and management when I let go of that super-preparedness. Because I’m never going to be fully ready, I’m as ready as I’m going to be. If anything, I focused on learning who all on my team was the “go-to person” for databases or Kubernetes or IAM permissions or what have you. When I don’t know the answer, I focus on staying calm and coordinating the people who might have the answer. When I keep a clear head, I’m able to pick up clues as to what might be worthwhile to brush up on after the incident is resolved.

Kristen: Not sure if you have dreams of being an engineering manager, Annabelle, but this response positively smacks of “leadership material” 😀

You mentioned in an earlier response that “software friction occurs in depth, devops friction occurs in breadth.” Can you explain a little more about this for me and our readers?

Annabelle: “Software friction occurs in depth, devops friction occurs in breadth” – that’s probably a wild overgeneralization. But I’m thinking of how, when I was solely focused on one or two domains as a software engineer, I was best served by deeply understanding the full stack of that particular problem space. If I could cobble together a script that made my particular tests run faster, that was a huge benefit. However, as a devops engineer I find myself tripping over project-specific idiosyncrasies.

For example, when I was making the transition from software to devops, I was a big fan of AWS CDK (and to a degree, I am still a fan!). CDK is an Infrastructure as Code (IaC) tool very similar to Terraform, but it is written with traditional software languages like TypeScript and Python. I wrote all of my teams’ infrastructure with AWS CDK, and for those projects, it was great! The app was written in Typescript, the infrastructure was written in Typescript, and the developers were closely involved in the infrastructure maintenance. However, when the larger DevOps team tried to implement organization-wide updates across our IaC (like updating mandatory tags), we had to chase down infrastructure written in multiple tools, maintained in multiple repos, and deployed in multiple ways. Grappling with all of these configurations is tricky, even if each configuration serves that particular software team well.

Like I said, though, pretty broad generalization. This isn’t to insinuate that software engineers are inherently selfish in their coding practices, or that devops engineers are mandatory fun-haters!

Kristen: Okay, that makes so much sense - thanks for clarifying that! Should we make a shirt that says "DevOps Engineers are NOT mandatory fun-haters"!? I feel like this could be a big seller at KubeCon…

Annabelle: The shirts would practically sell themselves!

Kristen: What kind of work do you do as a DevOps engineer to remove friction around CI/CD processes for the teams you support?

Annabelle: A good CI/CD pipeline strikes a balance between thoroughness and speed. In other words, you want to vet what you’re sending to production, and you want to be able to validate how it was vetted later on. But an overly long and complicated process can cause understandable frustration!

I work with my teams to determine which processes can run in parallel and which need to be sequential. For example, in many cases all tests can run simultaneously; unit tests won’t conflict with integration tests or snapshot tests. But if you also have end-to-end testing, or multiple suites that make changes to a test database, you don’t want to risk race conditions by running those all at once.

When I’m scaffolding new pipelines, I like to start by focusing on the run conditions. Each job will simply start with an echo command saying “I’m the database migrations” or “Docker build goes here”. That way, I can make sure the DAG (short for Directed Acyclic Graph) logic is working exactly as I expect. Once that’s set, I can tackle actually adding the migrations or the build in bite-sized chunks.

As far as decreasing build times, I’ve become a big fan of utilizing multi-stage Docker builds. Depending on how you structure your Dockerfile, you can rely on cached layers for less-frequently changed files. You can also maintain separate images for, say, testing versus production—rip out the tests, dev dependencies, and whatnot from your production image and you’ve got a smaller image that’ll ship faster.

Full disclosure, creating a multi-stage image doesn’t always save me tons of time. But starting that as a practice did help move Docker images from “magic boxes of computer stuff” to “what exactly do I need to run this program?” So still a worthwhile exercise, in my opinion.

Kristen: I’ve come to really appreciate and (full disclosure…) just even understand the value of layer caching in the build process. Depot just released a remote caching service, in fact, that utilizes a build cache to implement incremental builds and accelerated tests. It’s wild how much faster these builds are running using this strategy.

Alright, Annabelle - one final question for the road: What developer tool most helps you get shit done? If you had complete control over what dev tooling you use (and maybe you do!), which dev tool would be non-negotiable?

Annabelle: This is tough – there are a lot of tools I love! But many of them fit into the category of “strong opinion, loosely held.” I love Obsidian for note-taking and Typescript for development, but I can be happy with any link-friendly notes app or typed language. So, if we throw “non-negotiable” in there, I’d have to go with my Kubernetes tool of choice: K9s. It strikes the perfect balance between friendly UI and bare-bones CLI, so I can quickly navigate my clusters or drill into a particular resource. It was one of the first things I set up on my laptop when I started my new job.

If I may, I want to give an honorable mention to the actual first thing I installed: my favorite VSCode theme! It surprised me how quickly having a familiar environment helped me feel empowered to navigate a new codebase. I think it’s the digital equivalent of setting up photos and knick-knacks on your desk to make it feel homier. There might not be a quantifiable impact of installing one theme over another, but having a developer experience that feels uniquely yours (no matter how minimalist or maximalist) can make all the difference.

Related posts

- Introducing Developer Experience at Depot

- Developer Experience: Past, Present, & Future

- Dialogues in DevEx: A conversation with Nic Pegg