Prologue

Automating macOS is notoriously hard. Each year Apple takes a step in the right direction, but there is still a long road ahead. When the Virtualization Framework came out with Big Sur, the CI industry finally got a somewhat stable and usable tool to standardize macOS workloads. I say "somewhat" because it's far from perfect. Since macOS virtualization is such a niche area, there are only a handful of experts in the field. The documentation is lacking, and more advanced hacks and use cases tend to spread through closed Slack communities, X threads, or GitHub issues.

But technical challenges are only part of the story, the other part is licensing. Apple makes it hard for providers to offer macOS in CI economically. There are basically three main restrictions a CI provider needs to adhere to:

- Virtual machines must run on Apple hardware.

- Only 2 instances of macOS are allowed to be virtualized on a server at one time.

- Mac hardware must be leased for a minimum of twenty-four (24) consecutive hours.

From Depot's perspective, restriction #3 is the most important, as it applies to AWS as well. AWS is forced to offer EC2 macOS instances as dedicated hosts that need to be reserved (and paid for) for a minimum of 24 hours. Mac hosts in AWS are scarce resources, and there are frequent capacity issues.

Even stopping an instance takes 2+ hours because of the so-called scrubbing process, which wipes all customer data from the physical host. EC2 macOS is not something you can just quickly start and stop; these are designed as long-running workloads.

The only way for us to offer macOS as an ephemeral workload is to utilize VMs on top of the long-running EC2 Mac host. Virtualization always means some degree of performance penalty, but in the case of disk I/O, EBS is the main culprit. As the EC2 macOS offering and EBS evolve, we circle back from time to time to evaluate performance gains.

In this post, I'd like to showcase our latest measurements and walk you through our process for finding a cost/performance optimum.

The setup

I chose the following setup as the baseline for the measurements:

| Hardware | mac2-m2 (us-east-1) (8 cores, 24GB RAM) |

| Software | macOS 15.6 (24G84) |

| VM | macOS 15.6.1 (24G90) |

| Disk setup | gp3, 8000 IOPS, 1000 throughput |

I decided to run both synthetic performance tests and iOS build workflows which resemble real-life workloads.

Synthetic

For synthetic tests, I was using sysbench in the following setup:

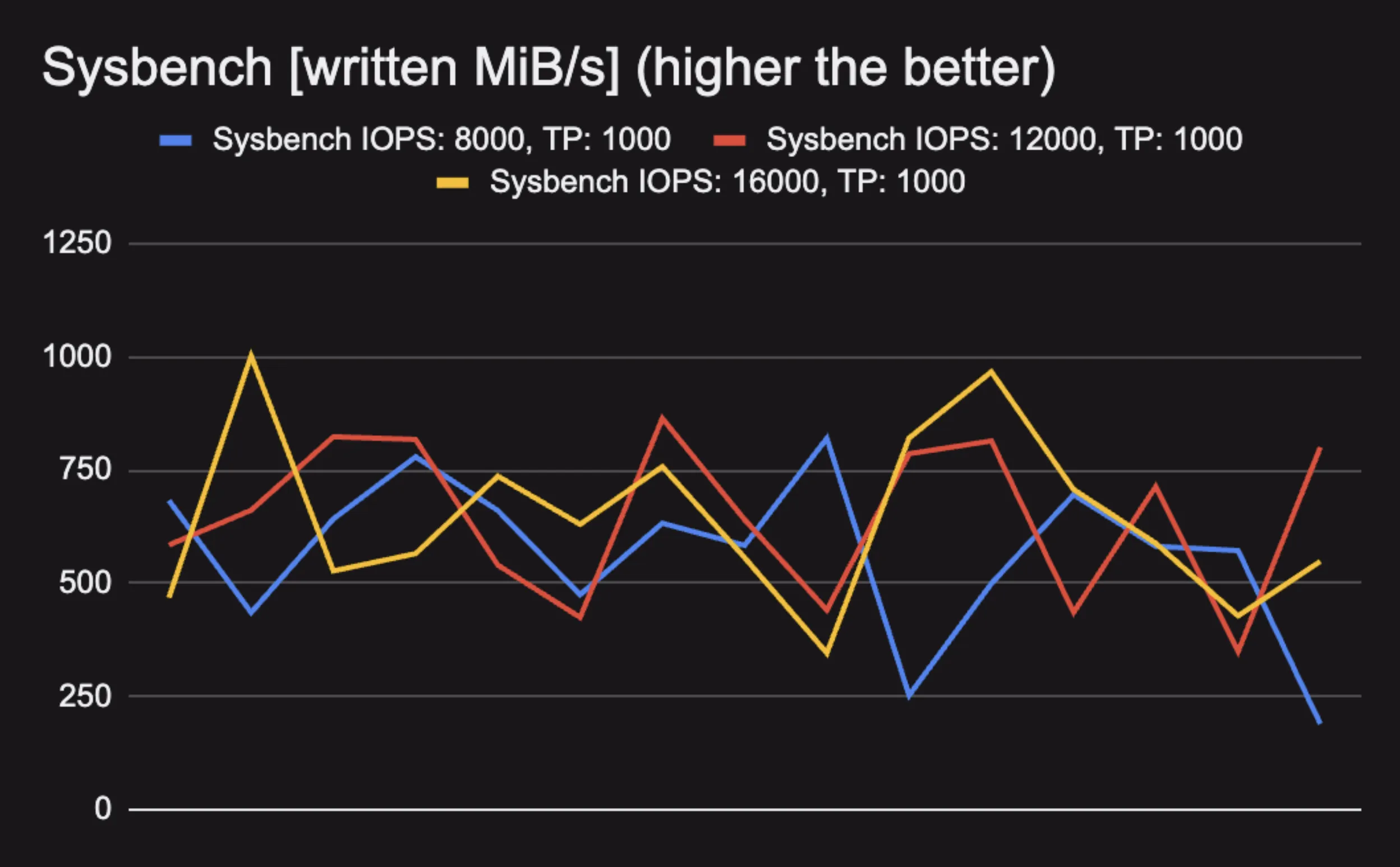

sysbench --file-test-mode=seqwr fileio run --threads=8 --time=30Of course, synthetic tests are by no means accurate indicators of "real life" performance, but they're perfect for establishing reference points that you can compare against later. The metric I chose for these tests was "Write throughput" [written, MiB/s].

"Real-life" workload

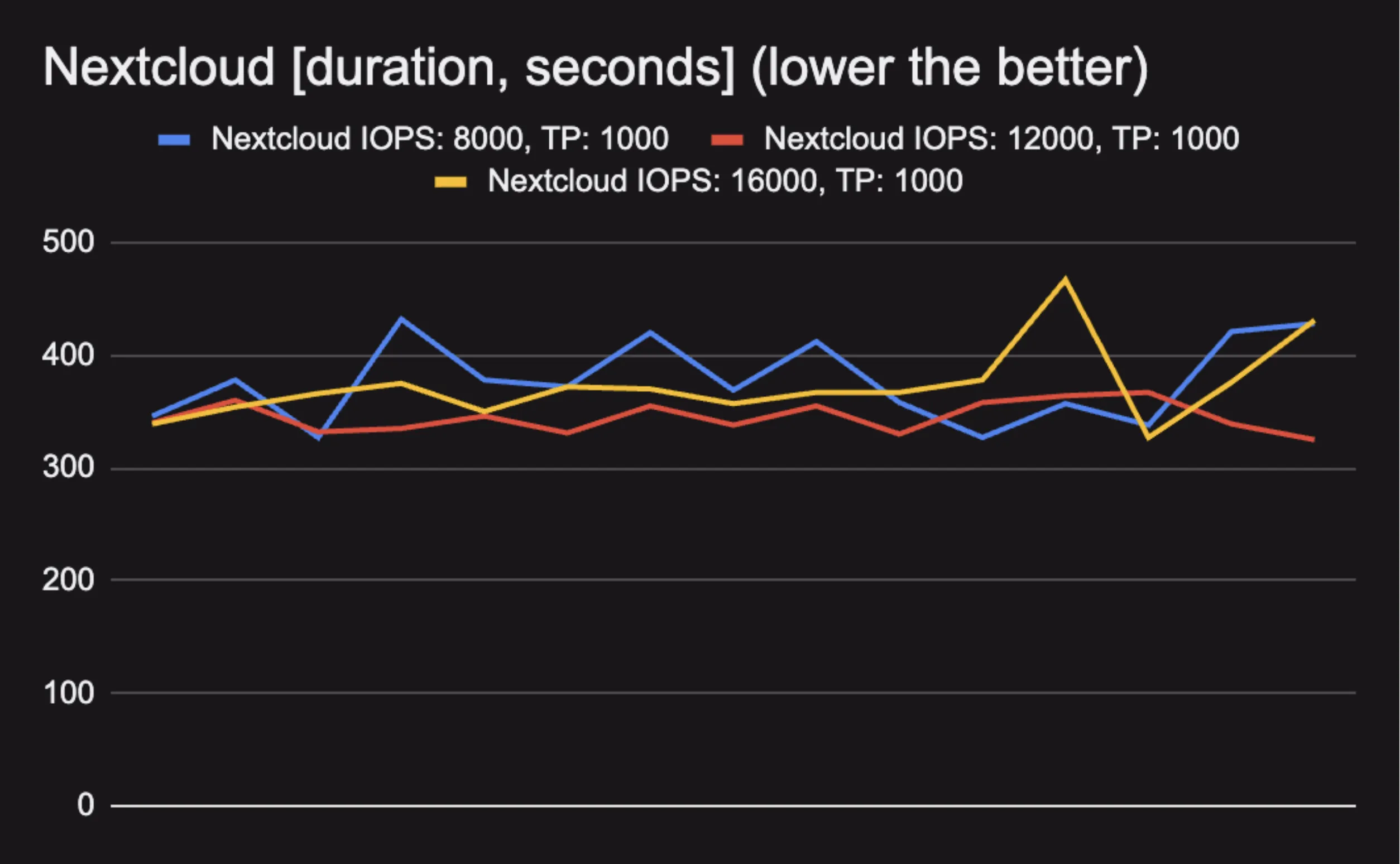

I've conducted iOS build measurements on a Nextcloud fork (with caching disabled). I chose xcode 16.4 arch=arm64,platform=iOS Simulator,OS=18.6,name=iPhone 16 as the xcodebuild configuration.

Since the baseline throughput was already fairly high, I decided to measure how increased IOPS influences build performance. Given that the test workflow performs compilation (reading numerous small source files and headers, writing many small object files, and handling frequent file metadata operations), I expected the workload to be I/O-bound anyway.

Measurements

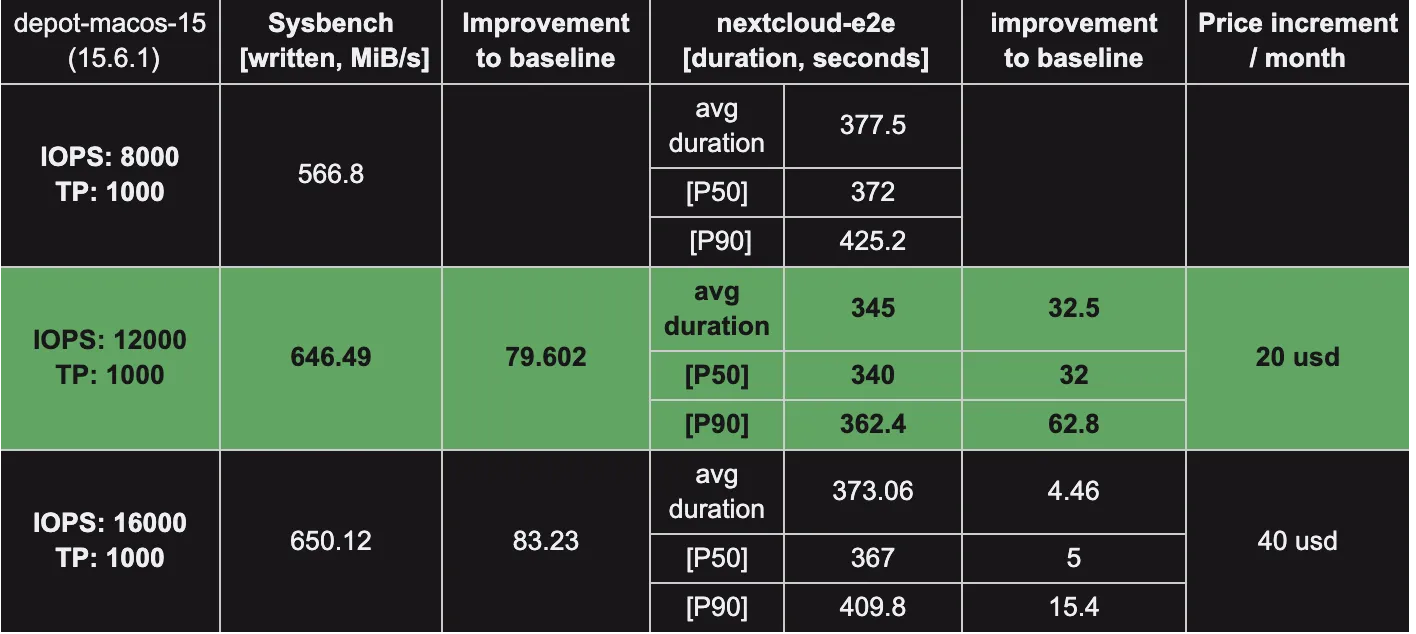

Surprisingly, even though the 16000 IOPS disk configuration performed better than the baseline, it consistently performed worse than the 12000 IOPS configuration. Based on our data, the measurements did not saturate the 8 Gbps EBS bandwidth the instance comes with, so our test workload's build characteristics probably don't benefit from additional I/O speed. We need to investigate further to understand why this is the case. If you have any guesses or insights, please let us know in our Discord community!

One thing is clear from the measurements: increased IOPS improves build performance consistency, as indicated by the p50 and p90 values.

Caveats

Two lesser-known factors are important to keep in mind:

-

Let me quote AWS:

When you create an Amazon EBS volume, either from an EBS snapshot or from another EBS volume (volume copy), the data blocks must be written to the volume before you can access them. For volumes created from snapshots, the data blocks must be downloaded from Amazon S3 to the new volume. For volume copies, the data blocks must be copied from the source volume to the volume copy. This process is called volume initialization. During this time, the volume being initialized might experience increased I/O latency and decreased performance. Full volume performance is achieved only once all storage blocks have been downloaded and written to the volume.

This means that in order to conduct reliable measurements, we first have to either read or write the full EBS disk. There are various ways to do this, but simply writing or downloading large files to disk works fine.

-

You may have noticed the inconsistency and fluctuation between test runs on the graph. Modern Macs with M-series chips are equipped with performance and efficiency cores. The Virtualization Framework assigns cores to the VM transparently, and there's no way to influence this decision. Depending on which cores the framework assigns to the workload, we might see different performance.

For those who would like to dig deeper into the topic, here are two well-written and informative posts from The Electric Light Company:

- How does macOS manage virtual cores on Apple silicon?

- Virtualisation on Apple silicon Macs: 4 Core allocation in VMs

Take two

One of our top requests when it comes to macOS runners is to improve build performance consistency. So while we were at it, we took a look to see if we could pinpoint anything within the VMs that might help in this regard.

As it turns out, we found a few CPU-hogging processes that we were able to eliminate. We also discovered a regression in Sequoia that had rendered some of our automated optimizations useless. When active, these processes often perform I/O-heavy work that chokes build performance.

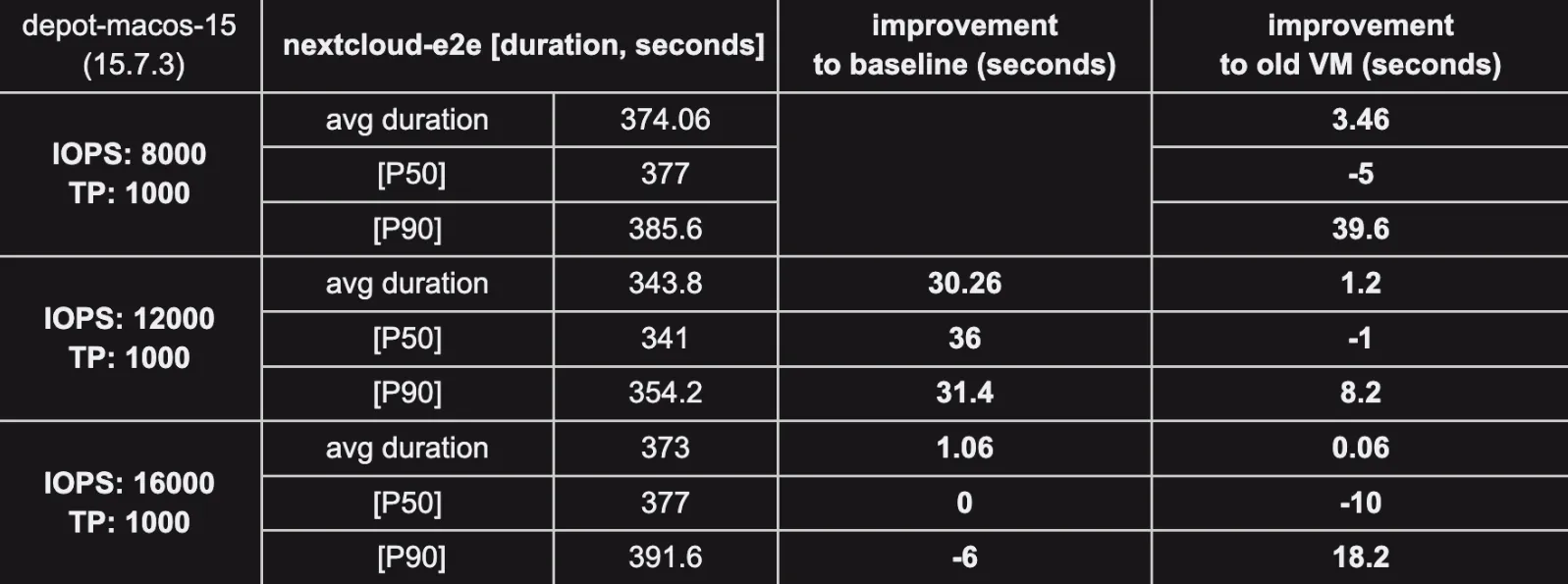

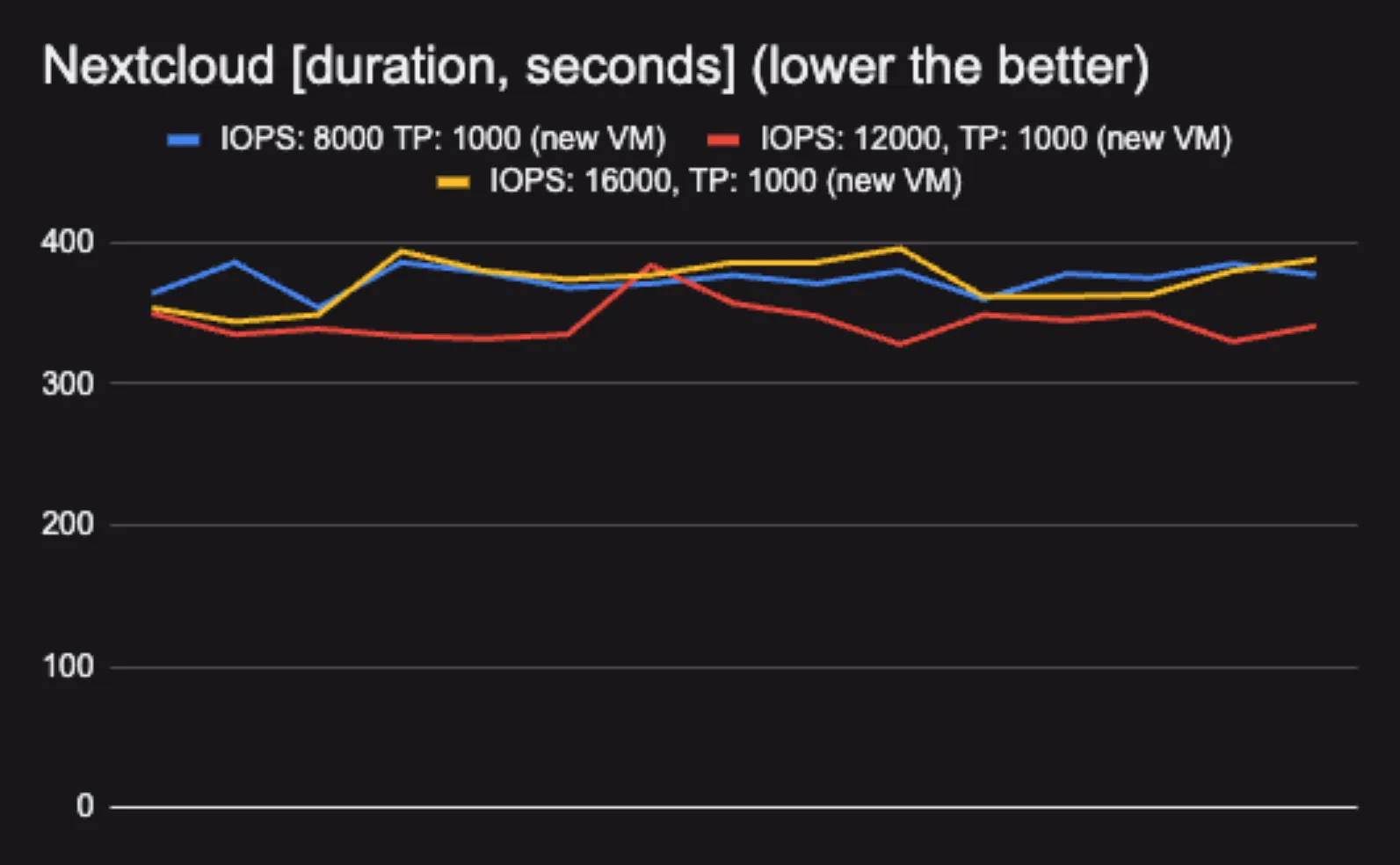

We've built a new macOS 15 VM (with updated Xcode versions) incorporating these fixes, and decided to redo the measurements. This time we omitted synthetic tests and instead concentrated on real-life workloads.

Let's see what the numbers show! First of all, the new VM version seems to indeed decrease the p90 outliers, which means build performance volatility has improved. The 12000 IOPS disk configuration brings great improvement across all metrics compared to the new VM baseline. It even shows slight gains compared to the old VM setup with the same disk properties. As we saw previously, the 16000 IOPS configuration performs below expectations.

The good news is that the new VM version combined with the 12000 IOPS disk configuration seems to be an amazing combination.

Now take a look at the visualization:

As you can see, the spikes are gone and the overall variance is much lower. The baseline chart (8000 IOPS) has improved remarkably with the new VM.

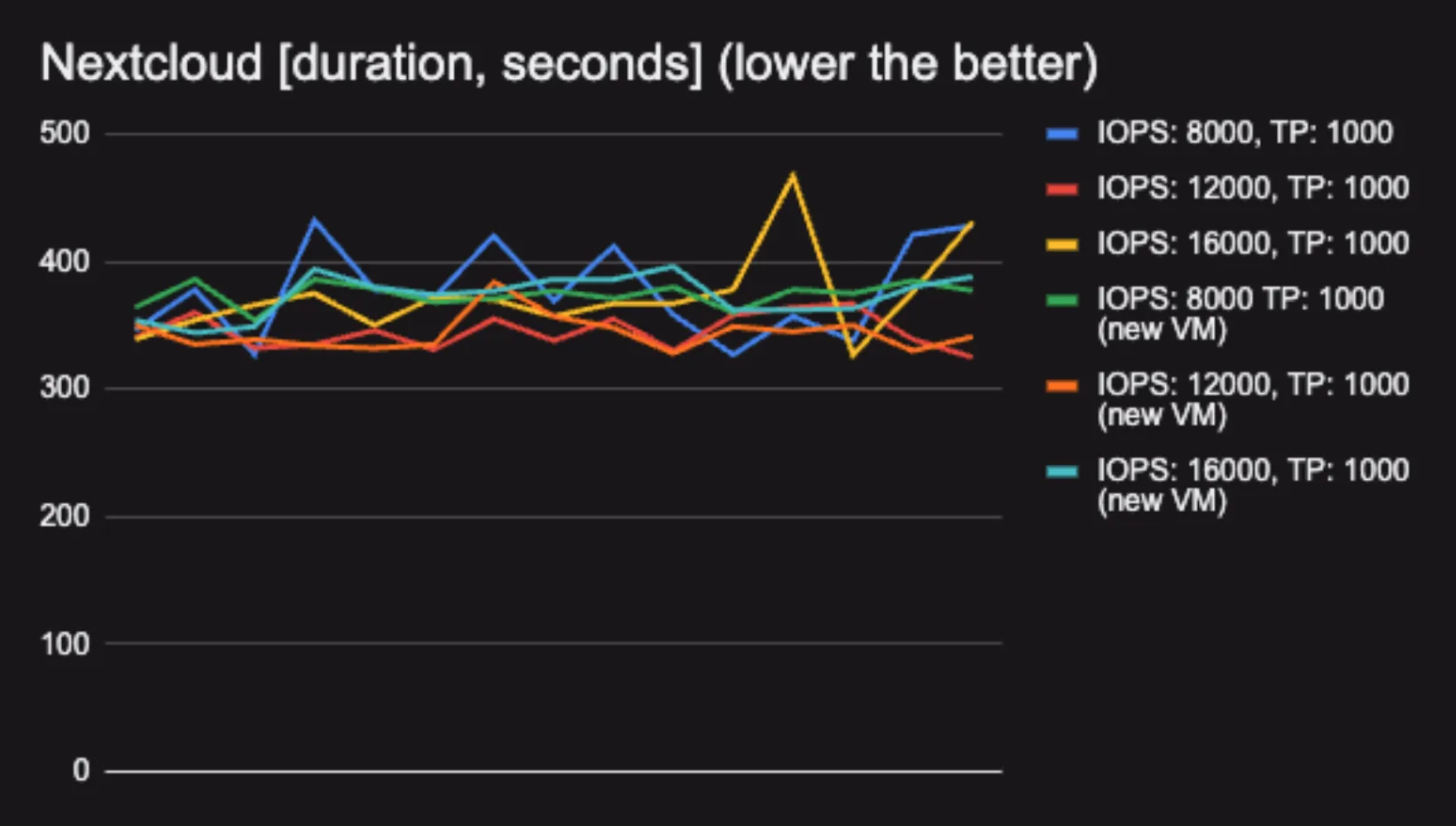

And finally a blended graph to show all Nextcloud measurements displayed on the same chart:

The 12000 IOPS, 1000 MB/s throughput disk configuration with the new VM is the absolute winner. But beyond that, it clearly shows that increased IOPS leads to more predictable build performance.

Conclusion

For me, the main lesson was that in order to boost build consistency and bring down p90 numbers, increasing IOPS is a tool we can use, but not mindlessly. The more we know about our customers' build characteristics, the better decisions we can make to maintain a healthy cost/performance ratio.

We'll incorporate these findings into the macOS runners, and as always, we'll continue to improve our VM images to make your builds faster. Until next time!

FAQ

What IOPS configuration performed best for iOS builds on EC2 macOS instances?

The 12000 IOPS with 1000 MB/s throughput configuration combined with our new VM version gave the best results. Surprisingly, 16000 IOPS consistently performed worse than 12000 IOPS, even though it didn't saturate the instance's 8 Gbps EBS bandwidth. We're still investigating why, but the data clearly shows 12000 IOPS is the sweet spot for this iOS compilation workload.

Why do I need to initialize my EBS volume before running performance tests?

When you create an EBS volume from a snapshot or another volume, the data blocks must be written to the new volume before you can access them at full performance. During this initialization process, the volume experiences increased I/O latency and decreased performance. To conduct reliable measurements, you need to either read or write the full EBS disk first. Simply writing or downloading large files to disk works fine.

Will these IOPS findings apply to other build types besides iOS?

Our testing focused specifically on iOS builds using Xcode, which involve reading numerous small source files and headers, writing many small object files, and handling frequent file metadata operations. If your build workflow has similar characteristics (lots of small file operations), you'll likely see similar benefits from the 12000 IOPS configuration. But different build types might have different optimal configurations. Test with your specific workload to find your optimal configuration.

Can I control which cores the Virtualization Framework assigns to my macOS VM?

No, there's no way to influence this decision. The Virtualization Framework assigns performance and efficiency cores to the VM transparently. This is one of the factors that contributed to the inconsistency and fluctuation we saw between test runs in the graphs. Depending on which cores the framework assigns to the workload at any given time, you might see different performance characteristics.

Related posts

- macOS GitHub Actions Runners are now twice as fast

- Uncovering Disk I/O Bottlenecks in GitHub Actions

- Accelerating builds: Improving EC2 boot time from 4s to 2.8s